Lessons from a dark part of ancient history

In 536 AD, a lot of the world was completely dark for 18 full months. This sounds bonkers but it’s true! The sun was literally blocked by some kind of weird fog so that crops failed and people subsequently went hungry and died. This fog blanketed the Middle East, Europe, and parts of Asia. It was huge and devastating and completely bewildering (one imagines) to the people who did not see the sun for more than a year.

I first heard about this story over a year ago but I think about it frequently. What must it have been like to be those people, covered in darkness for months and months, with no apparent rhyme or reason? What did they tell each other? What did they tell their children? How long did their hope last, if it lasted at all? I think too, about how utterly alone they were. There was no way to communicate with people beyond their borders, so each little hamlet and town must have thought they were totally alone in the dark.

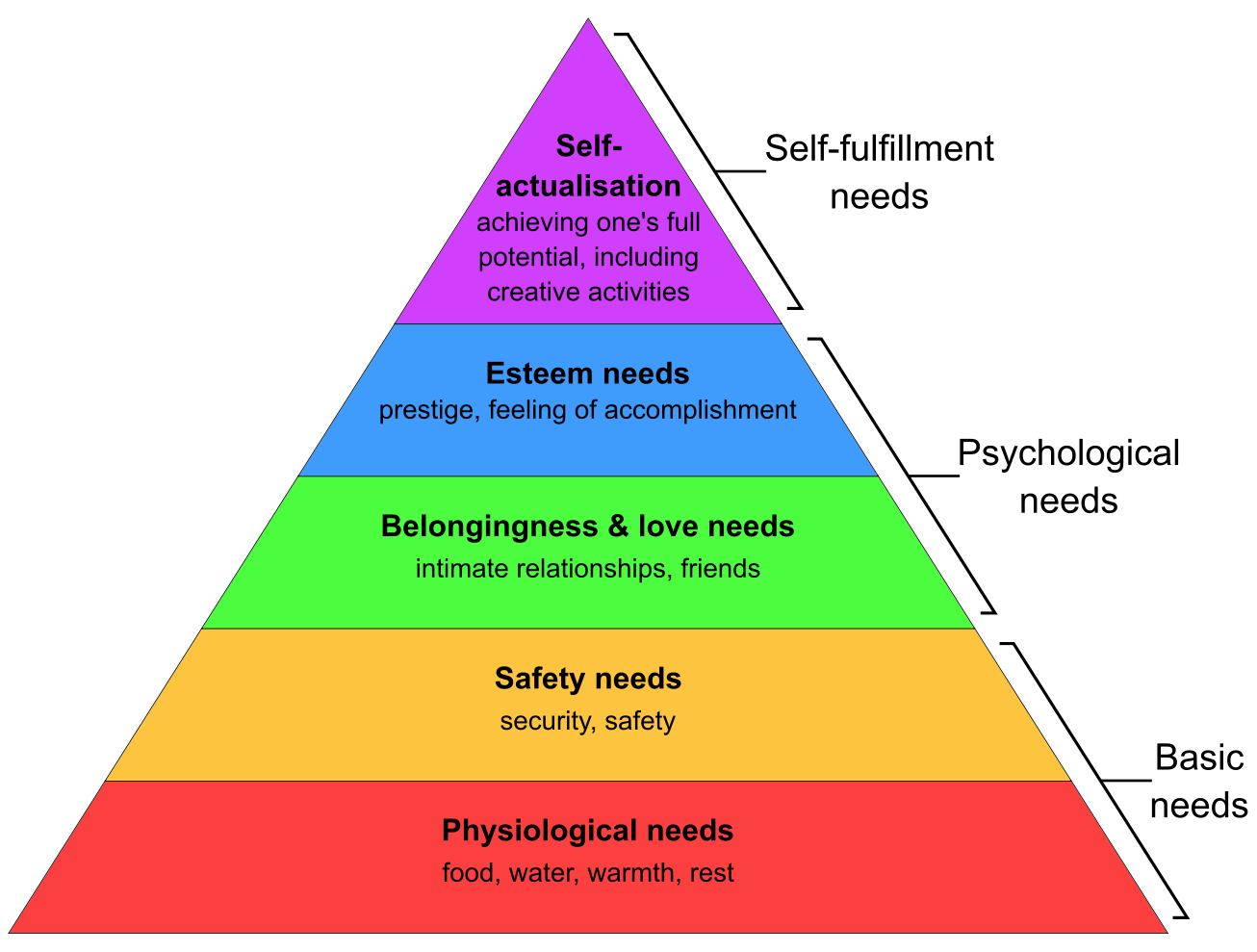

While we may not be in literal darkness, many of us feel that way at this moment in time. There is so much ambient grief and anxiety and distress, it’s difficult not to feel it seeping into you. The usual coping skills are harder to access at times like these. Everything feels harder, actually. It’s hard to feel so overwhelmed by the state of the world and the winter and illness and anxiety and and and. We are all, collectively, overwhelmed by darkness.

However, unlike the people in 536, we are not alone in our distress. We are not isolated in our tiny towns, wondering if the world is ending or if we’ve been cursed. We can reach out to each other and get support, even if there are no quick fixes or easy answers. We are not alone; you, reading this, are not alone. We can find the light by being with each other and seeking joy in the darkness.