The Good, Medium, and Bad days checklist

One truth about both grief and chronic pain (my two areas of expertise) is that some days are good, some days are bad, and some days are neither. Categorizing the days that way isn’t my attempt to judge them, though that’s what it sounds like. Instead, it’s my way of helping my clients figure out how to manage based on what kind of day (or moment) they’re having.

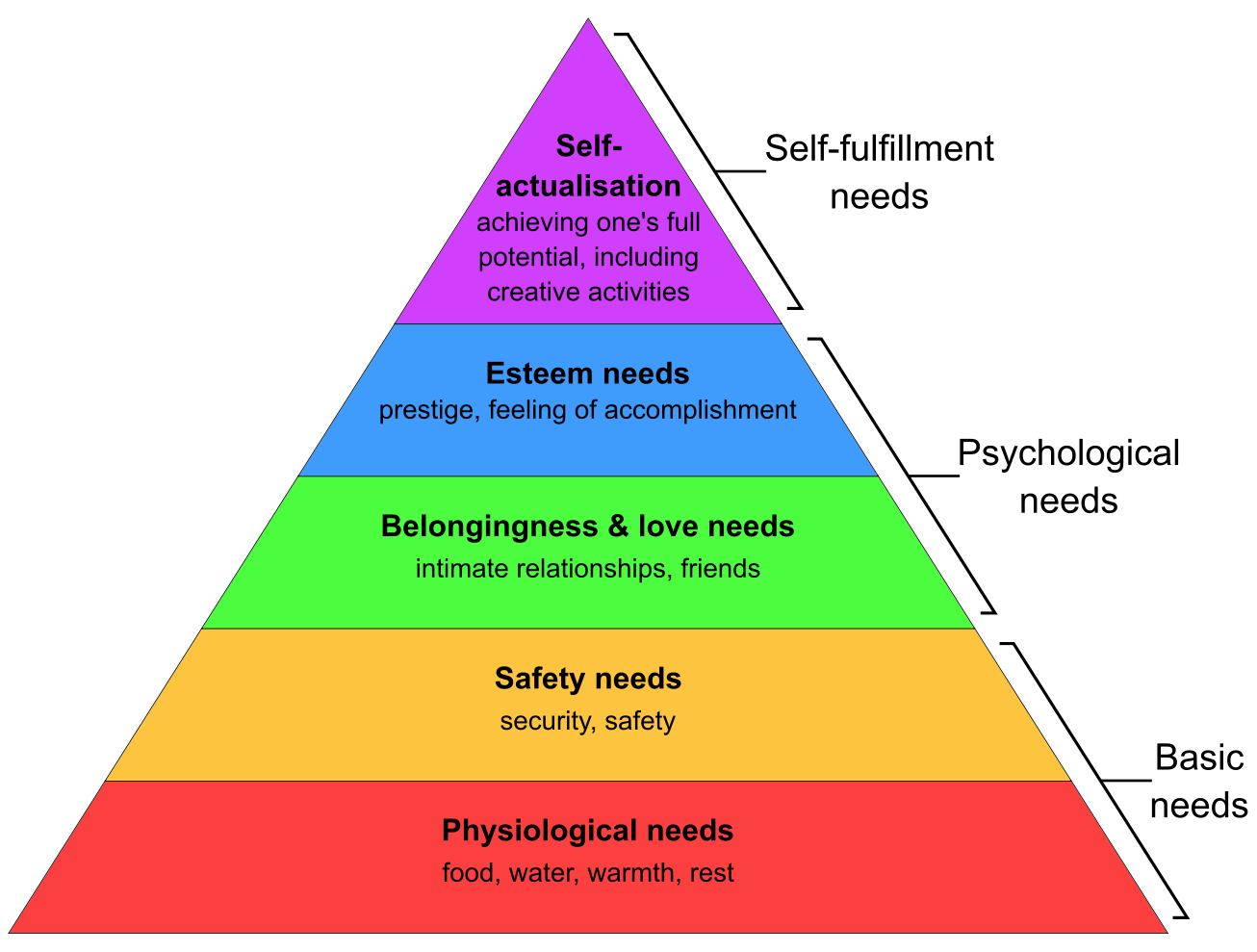

I hear a lot from my clients about whether or not they’re being “productive.” This is a word I hate. You are not a factory that has to churn out a certain amount of parts every day in order to keep functioning. You are a person who sometimes has easy days and sometimes has hard ones. If you are living with chronic pain or suffering a bereavement, you are allowed to not “accomplish” something every minute of every day, or even once every day. Sometimes it’s a struggle to wash your hair or make an important phone call or exercise. It’s ok for even “easy” things to be hard.

Easy for me to say, right? We get a lot of messages about our worth from a lot of different sources and for most of us, it boils down to this idea of productivity. I can’t undo any of that just by telling you it’s ok to have a bad day. What I can do is offer an alternative to the self-berating some people do when their pain or their grief prevents them from being productive.

Instead of starting with judgment (“I didn’t do anything today, I’m useless, I wish I had…” etc.), start with making a list. Actually, make three lists: what can I do on a good day? What can I do on a bad day? What can I do on a medium day? A bad day might consist only of eating and drinking and brushing your teeth. A good day might be an endless list of possibilities. There’s no right or wrong, only what you are capable of doing depending on what kind of day you’re having.

This might sound kind of silly but let me explain how it can help. If the only things on the list on a bad day are tasks you’re able to complete, you cannot berate yourself for not doing more. You did the things you were able to do on this particular day. On the flip side, the list of good day activities doesn’t have to be wholly completed on a good day. It can be filled with options: a good day might mean taking a walk with a friend or sitting down to pay bills but it doesn’t have to be both of those. There will be more good days to do more things on the list.

Changing the way we view ourselves and our worth is not a quick fix; it’s an ongoing practice made of many small habits and tasks. Instead of the usual cycle of self-recrimination, try something new. Make a list. Give yourself grace. Better days will come.